Lanarkshire

Cambuslang

Kirkhilll church

Now mainly a suburb and dormitory town for Glasgow, Cambuslang was the scene of a great revival in 1742 under George Whitefield and William McCulloch (1691-1771), minister of Kirkhill church in Vicarland Road (G72 8LL).

Close to the church in Cairns Road is Cambuslang Public Park, which forms a natural amphitheatre, known as the Preaching Braes. This was where Whitfield preached in the open air to large crowds in the summer of 1742, in an event that became known as the Cambuslang Wark [Work]. A stone memorial erected in 2008 records that In this place George Whitefield led congregations of many thousands in prayer and worship.

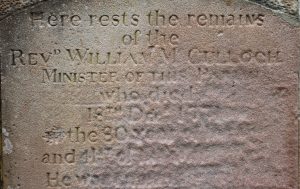

The tall-spired church is currently undergoing conversion into a children's nursery, with the main architectural features being retained and restored. McCulloch is buried in the churchyard. His gravestone, much eroded by the elements is set into the wall on the south side of the church. The inscription, now illegible, reads He was eminently successful in preaching the gospel.

William McCulloch gravestone

McCulloch might an unlikely candidate to lead a great revival. It was said that he was a conscientious pastor, but no great preacher, even unsure of his own calling. In Scotland, bi-annuual open-air "Holy Fairs" were held when members of neighbouring parishes came together for fasting, preaching and self-examination in preparation for Holy Communion. McCulloch's preaching at these events was said to send people running for the alehouse!

In 1741, reports of revival in England and North America were beginning to reach Scotland. George Whitefield preached in Glasgow on a tour to raise money for his orphanage in Georgia and members of McCulloch's congregation brought back reports of the meeting. At the beginning of 1742, two local working men, Ingram More and Robert Bowman, lobbied families in Cambuslang to ask McCulloch for a weekly lecture, which was arranged for Thursday evenings. On the third occasion, about 50 people experienced a strong conviction of sin and came back to the manse for further instruction. Numbers increased over several months, many experiencing strong emotions with loud cries and violent physical expressions. The revival reached a climax in August when McCulloch was joined by several other ministers, including George Whitefield, who preached to crowds of up to 30,000. Communion was served to 3,000 in two large tents and some 400 experienced conversion.

Blantyre

This was the birthplace of the missionary and explorer David Livingstone (1813-1873) and has of course given its name to a major town in Malawi, where much of Livingstone's life was spent.

Livingstone statue

His original home and workplace in Station Road (G72 9BY) has been converted into the David Livingstone Centre, and is now open to the public following a complete refurbishment. Outside is a dramatic sculpture of Livingstone being attacked by a lion. The creature is leaping up, about to fasten its jaws onto his left arm, as two African servants are brushed aside, all three men with expressions of horror and desperation. The incident which took place in 1844 in Mabotsa in present day South Africa left Livingstone with a permanent injury, never gaining full use of his arm. He shook me as a terrier does a rat, he wrote of the event.

Kilsyth

Kilsyth church

In 1839, a great revival took place in the town under the preaching of Robert Murray M'Cheyne (1813-1843), Andrew Bonar (1810-1892) and William Burns (1815-1868). This was centred on the parish church in Church Street (G65 0NF). Built of light grey stone with a tower and blue-faced clock, there is nothing outside to remind us of this event. Unfortunately, like most Scottish churches, it is kept locked outside service times.