Edinburgh

Princes St

Right at the heart of Edinburgh is the unmissable Scott Monument, featuring a seated statue of Sir Walter within a vast gothic-style canopy. Even for such an iconic figure as the famous novelist, whose works capture the romance and drama of Scotland's history, it seems a little overdone.

Livingstone statue

Scott was a Church of Scotland elder at Duddington. When ill, he asked his servant to bring "the Book". When the servant asked which book, Scott replied: There is only one Book - the Bible! The Bible is the Book to live by and the Book to die by. Therefore read it to be wise, believe it to be safe, practise it to be holy.

Later in the nineteenth century, it was thought that another famous Scotsman, whose achievements exemplifed the courage, faith and enterprise of the country, also deserved to be remembered here – David Livingstone. A statue of the celebrated missionary explorer stands within the gardens of the monument, but it's a modest affair compared with Scott. It shows him dressed for jungle travel, with leather belt, boots and holster, a coat knotted casually over his shoulders, his stick resting on the ground and the Bible held out in one hand. The skin of a lion is draped over a stump behind him, recalling the famous incident when he was attacked by a beast which had just been shot, but left him with a permanent injury to one arm before it expired.

Old Town

St Giles Cathedral

St Giles Cathedral

St Giles may not have the architectural splendour of its English counterparts, but its significance in Scottish church history is as great as any in England. In this respect it can be compared to Westminster Abbey in London, with memorials to celebrated Scots, as diverse as the writer Robert Louis Stevenson and pioneer of anaesthetics James Young Simpson, as well as pivotal figures in the spiritual life of Scotland, like John Knox and Thomas Chalmers.

The central position of the tower gives the nave and choir equal length, a feature that enabled the cathedral for a time to have separate congregations at the east and west ends. There was even a third congregation meeting in what is now an extra aisle on the south side, from which various chapels lead off. From the outside, we can see the eight flying buttresses over the tower meeting centrally to form an open structure, known as a crown spire.

Founded in 1124, St Giles was twice reduced to ashes by invading English armies, burn marks on the stonework apparently visible until nineteenth century restorations. In the sixteenth century, the cathedral became the focal point of the Scottish Reformation. In 1558, with Scotland fast adopting a strongly protestant theology, the statue of St Giles was removed from the church and thrown into Edinburgh's putrid Nor' Loch, today the site of Princes Street Gardens.

In 1559, John Knox, lately returned from exile in Geneva, marched into St Giles and preached there for the first time. The following week he was declared minister and the cathedral was stripped of all its Catholic ornamentation. In 1560, the Scottish parliament declared Scotland a protestant country and St Giles thus became the founding church for world Presbyterianism – with no bishops, but each congregation governed by elders or presbyters, and ministers chosen by the members.

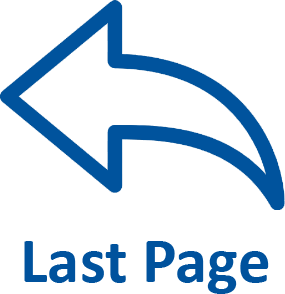

Jenny Geddes stool

The next major crisis in Scottish church history came 80 years later. In 1637, Charles I attempted to align the Church of Scotland with the Church of England by appointing bishops and imposing the use of the Anglican Prayer Book. This precipitated a major disturbance: on 23rd July of that year, James Hannay, dean of Edinburgh, appeared in a surplice and began to read the service according to the Anglican liturgy. A riot broke out with clapping and shouting by local women. When Dr Lindsay, bishop of Edinburgh, rose to call for calm, Jenny Geddes, a local vegetable seller, hurled a stool at the preacher with the cry Daur ye say mass in my lug? and the whole congregation rose in uproar. Magistrates were called to escort the prelates from the cathedral and church services were suspended for a week. Later that night, a large group of women spotted the bishop and his friends and chased them down the street with sticks. While church leaders distanced themselves from this behaviour, calling the protesters a rascal multitude, these events led the opponents of the king's policy to draw up the National Covenant, signed in Greyfriars church in 1638.

A memorial plaque to Jenny Geddes was placed in the Moray Aisle in 1886, and in 1992 it was joined by a bronze stool, known as a “cutty stool”, sculpted by Merilyn Smith. The sculpture is entitled Dux femina facti [A woman was leader of the deed], and was financed by subscriptions from forty women. It seems they may have celebrating Ms Geddes as a feminist icon, rather than for her protestant ideals!

A 19th century stained glass window on the south wall shows John Knox (1514-1572) preaching the sermon at a funeral in 1570. When he died two years later, he was buried in the kirkyard here, but some time later his remains were reinterred in an unmarked grave at Greyfriars. Knox also has a statue in the north aisle, dating from 1904. There is an account of his life, quoting his famous dictum Give me Scotland or I die.

A marble memorial with a bronze profile portrait celebrates Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) as Christian orator, theologian, patriot, professor of divinity at Edinburgh University. Chalmers is particularly remembered as one of the initiators of the Great Disruption, by which the Free Church of Scotland separated from the main body of the church, principally over the appointment of ministers.

Many of the memorials on the north side relate to the First World War and the role of the Royal Army Medical Corps is given particular prominence. One memorial commemorates the surprisingly large number of Scottish women nurses who lost their lives, presumably from a combination of disease and accidental military action.

William Smith memorial

In one of the chapels on the north aisle is a memorial plaque to Sir William Smith (1854-1914). He was a Scottish businessman and Sunday school teacher, who in 1883 founded the Boys Brigade at the Free Church Mission Hall in Glasgow. As a uniformed youth organization which emphasised Christian character, it was used as the model for Baden Powell's more secular Boy Scouts.

An oval tablet on stairway leading down to the cafe remembers Wellesley Bailey (1846-1937), founder of the Leprosy Mission. Bailey was an Irishman who had originally travelled to India with the intention of joining the police, but seeing the condition of leprosy sufferers, he applied his Christian faith to addressing their treatment and relief. He lived in Edinburgh from 1882 to 1886, where he worked as a secretary for a Church of Scotland mission.

John Knox House

John Knox's house

Halfway down the Royal Mile – midway between the Castle and the Palace of Holyrood – is the bizarre medieval building known as John Knox House. From the outside, its unusual shape and unique appearance suggests the setting of a fairy story or a fantasy film. Despite the name, it was apparently never owned by Knox, nor served as his manse, but it is believed he spent time here as a sick man in his final months and may have died here. The actual site of Knox's manse - in Warriston's Close, a narrow lane off the High Street near St Giles - is marked by a plaque.

At the time of Knox, the owner was James Mossman, a goldsmith and jeweller to the royal house, and his wife Mariota Arres. Ironically, Mossman was a Catholic loyal to Mary Queen of Scots, and, following the siege and surrender of Edinburgh Castle in 1573, was hanged for counterfeiting and treachery.

Even with no historical links, the house would be a place of great interest. It projects onto the street with one facade looking up towards the Castle, with the other facing across the road. An external staircase to the first floor gives an excellent view towards Holyrood and the coast beyond. There are four storeys with overhanging gables, and a host unusual features on the outside. These include the letters IM MA, initials of Mossman and his wife, with a family crest. A gilded sun with the words Theos, Deus, God shines onto the bearded figure of Moses, who is kneeling on a sundial at the corner. There are gilded wreaths either side of the first floor window, while above is a circular recess with urns either side – perhaps a later classical flourish. Best of all, running round two sides with gilded lettering is the command LVFE GOD ABVFE AL AND YI NYCHTBOVR AS YI SELF.

Inside the house, some exhibits tell the story of Knox and the Scottish Reformation, while others describe aspects of the goldsmith's trade and other crafts. An adjacent building serves as the Scottish Storytelling Centre.

J Knox house interior

On the ground floor, opposite the reception area, we can see the original stonework of medieval “luckenbooths”, lockable stalls facing the street which were rented out as shops. Upstairs there is a display entitled The Word and the Book, emphasising the importance of the Bible in Scottish history. Among items on display is a rare original copy of the Bassandyne Bible, the first Scottish printing of the English Bible in 1579, using the Geneva version. There are also copies of books written or owned by reformers including Theodore Beza and George Buchanan.

On the second floor, a room entitled Reformation and Revolution quotes various passages from the writings or sermons of Knox – on idolatry, preaching, education, obedience to the state – and then explains how these were implemented or interpreted. The top floor is called the Oak Room, which has been beautifully restored with panelling to represent the interior of a typical 16th century home. Here, dramatised versions of the exchanges between Knox and Mary Queen of Scots are being played. There is also a striking picture representing the offerings of Cain and Abel.

Greyfriars Church

Greyfriars Church

Visitors from across the world come to hear the moving tale of Greyfriars Bobby. When his owner, an Edinburgh policeman, died in 1858, the faithful Skye terrier kept watch at his master's grave until his own death 14 years later – cared for by the equally faithful sexton. Dog, master and sexton all lie here, their graves an important stop on the tourist itinerary.

For other visitors, the immense historical importance of Greyfriars, particularly as the scene of the signing of the National Covenant, is the main attraction, also as the last resting place of many of the giants in the story the the Scottish church, including George Buchanan and Alexander Henderson. Indeed, the bones of John Knox himself lie here, unmarked, after removal from the kirkyard of St Giles cathedral during redevelopments.

Formerly the site of a monastic order, the area was given to Edinburgh Town Council by Mary Queen of Scots as a burial ground. It served this purpose for some years before the construction of the church, begun in 1602 and eventually dedicated in 1620. There is a useful plan of the churchyard, marking the tombs of many prominent citizens (and one dog!).

George Buchanan's grave

The grave of George Buchanan (1506-1582), just to the north of the church and beyond its western end, is marked by a stone obelisk inset with a bronze bust of the scholar. Buchanan was an immensely significant figure at the time of the Scottish reformation. A man of great learning, he had studied in Europe and wrote major Latin works of poetry, history, law and constitutional politics, while moving gradually from a humanist position similar to Erasmus to a fully Reformed view. He was an adviser to the teenage Mary Queen of Scots, newly returned from France as widow of the young French king, but later a severe critic of her policies, especially after her marriage to the vain and foolish Lord Darnley. He also became tutor to her infant son, the future James I of England (and VI of Scotland). There is also a bronze plaque to Buchanan on the east side of the churchyard.

Alexander Henderson's grave

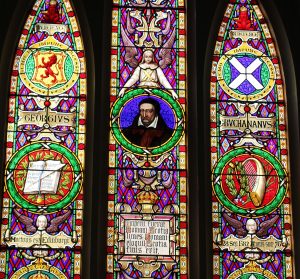

Not far away, close to the western wall and a little to the south, lies Alexander Henderson (1583-1646). His tomb is covered by a square stone monument, with a lengthy Latin inscription, badly weathered, but there is also a verse in English. Henderson was largely responsible for the text of the National Covenant, signed here in 1638. It was less than a century after the Reformation that the young Church of Scotland faced a new threat – this time from Charles I, and his sacramentally-inclined Archbishop William Laud. Their attempts to impose episcopacy and the Anglican Prayer Book on a Presbyterian Scottish church led to a series of wars and ultimately to the English Civil War, with its tragic outcome for the King. It was not just a religious matter – bishops had a significant secular role and their appointment was seen as interference in political affairs and against the civil liberties of Scotland. Henderson was a theologian and ecclesiastical statesman, who did his best to mediate between the disputing parties and on several occasions negotiated personally with the King, on whom he made a very favourable impression. Sadly, matters were unresolved and the Civil War still in progress when Henderson died in 1646.

On the eastern wall of the churchyard, on the left as you enter from the lower end of Candlemaker Row, is a large memorial to the Coventanter martyrs, many of whom died at Grassmarket close by. When we visited, it was undergoing a major restoration, covered in scaffolding and fabric. Another connection with the Covenanter period can be seen at the southwest corner of the kirkyard. Here, there is an extension of the burial ground in an area now fenced off and enclosed, but previously used as a prison. As explained on the notice, following the Battle of Bothwell Brig in 1679, Covenanter prisoners were held here for several months. Some were executed, some pardoned and some escaped, but the remainder were sentenced to be transported to the American colonies. However, their ship was wrecked in the Orkney Islands and most of the prisoners drowned. A few survived and managed to escape. (For Covenanter memorials throughout Scotland and beyond see www.covenanter.org.uk)

Inside the church itself, Greyfriars is plain, with very little adornment; its modest architectural qualities belie its great historical importance. It has a broad nave with octagonal columns and north and south aisles, but no transepts or side chapels. In 1718, an explosion blew out the west end of the church, after the city unwisely kept its store of explosives nearby. After pondering the problem of reconstruction, the church authorities eventually decided to divide the church in half with a wall down the centre, forming two congregations. The eastern part became Old Greyfriars, and the rebuilt west end New Greyfriars which explains the two adjacent front doors. This arrangement continued until the the two parts were reunited in the 1930s.

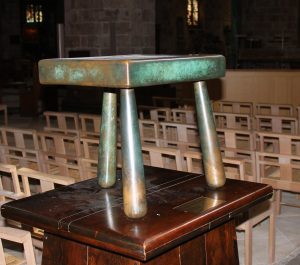

George Buchanan window

In the years following the Reformation. any kind of church adornment, including stained glass, was frowned on as reminiscent of Roman Catholicism, but this gradually changed in subsequent generations. Hence there is an impressive window to George Buchanan in the south wall. Another window commemorates Robert Traill (1603-1678), a significant figure in the events of the time. He became minister here in 1648 and preached before Charles II at his coronation by the Scots in 1651 (Charles seeking Scottish help to recover his throne after the execution of his father). In 1660 he engaged in a new Remonstrance, appealing for the rights of an independent Scottish church and supported the decision of the Covenanters to take up arms. He was arrested for High Treason, but was allowed to seek exile in Holland, from where he carried on a regular correspondence with the Covenanting minister William Guthrie of Fenwick. He was able to return to Edinburgh shortly before his death and is buried here.

The National Covenant

Other ministers who served the congregations here include Andrew Mitchell Thomson (1779-1831) and Thomas Guthrie (1803-1873). Thomson was a leader of the evangelical party in the Scottish church. Like his English counterparts linked to the Clapham circle, he promoted a wide range of reforming projects, supporting the immediate abolition of slavery. He was a co-founder of the Edinburgh Bible Society and promoted music in worship, for which he composed hymn tunes. He was minister of New Greyfriars from 1810 to 1814, when he moved to the newly founded St George's church.

Guthrie (1803-1873) was minister of Old Greyfriars in the early 19th century, but at the Great Disruption in 1843, he left to become one of the founding fathers of the Free Church of Scotland and first minister of Free St John's Church built in 1845, which is now St Columba's Free Church. He is also remembered as the founder of the Ragged School movement in Edinburgh – an unattractive name, but at least it provided a basic education for poor children who would otherwise have been illiterate.

In the south west corner of the church is the Visitor Centre, which has a small museum of items relating to the church, including an original copy of the National Covenant.

St Columba's Free Church

Strategically situated at the bottom of Castlehill, the church serves as a base for Christian Heritage Edinburgh – a small team who put up display panels and conduct walking tours throughout the tourist season. Well informed guides, sometimes in contemporary dress, give graphic descriptions of the most dramatic, and sometimes tragic, episodes of Scottish church and secular history. The panels here refer to the wider significance of Christian heritage in areas such as law, science, medicine, education, human rights and social reform. (See www.christianheritageedinburgh.org.uk)

Church of Scotland Assembly Hall

The first minister of the church (originally known as Free St John's) was Thomas Guthrie (1803-1873), an important figure in the Great Disruption of 1843, when a large proportion of the congregations of the Church of Scotland left to become the Free Church of Scotland. The main topic of contention was the right of church members to appoint their own ministers rather than having them imposed by the local patron. There is a prominent bust and memorial to Guthrie in the entrance lobby.

Immediately opposite St Columba's, is the Church of Scotland Assembly Hall. It was here that the American evangelists, D. L. Moody and Ira Sankey, conducted an important mission in the 1870s and also where the World Missionary Conference of 1910 was held. Following the great rise of missionary activity in the 19th century, it was hoped and believed that the whole world would have the opportunity to hear the gospel within the next few decades.

Grassmarket

Grassmarket

Today it may be a cheerful tree-lined street, with shops, bars and tourists, but its past is a story of tragedy, martyrdom and sacrifice. Grassmarket had long been the place of execution for common criminals, but is remembered particularly for the deaths of many Covenanters between 1661 and 1688, during the reigns of Charles II and his brother James II (VII of Scotland).

Their father Charles I had tried to impose the English prayer book and episcopal system on the Scottish church in 1637, leading to the signing of the National Covenant and provoking a series of conflicts which eventually led to the English Civil War, culminating in his own execution.

Covenanters memorial, Grassmarket

After the restoration of the monarchy, the later Stuart kings showed that past disputes over church government had not been forgotten or forgiven. During the Civil War, Charles II (then Prince of Wales) had made a pledge to honour the Presbyterian system of the Scottish church when he needed the support of the Scots against Oliver Cromwell, but this was forgotten after his restoration to the throne. This caused some Covenanters to renounce their loyalty to the king and to leave the Scottish church, often building “conventicles” in remote places, which was punishable by death. It was only after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the Catholic James II was deposed and replaced by his protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange, that the persecutions ceased.

At the eastern end of the street is a circular granite memorial, with a cross set in cobbles and the inscription On this spot many martyrs and Covenanters died for the Protestant faith. Nearby, there is a list of about a hundred men and women who were executed here or at other locations in Edinburgh, ending with the death of James Renwick in 1688, who is generally recognised at the last of the Covenanter martyrs.

Magdalen Chapel

Located in Cowgate and not particularly impressive from the outside, this may well be the place where the first assembly of the Church of Scotland took place under John Knox in 1560. It was built in 1541-44 as a hospice for a few poor men, and the meeting place for a guild of metal workers, known as the Hammermen. The tower and spire date from 1620. The assembly of 1578 was also held here under the moderator Andrew Melville (1545-1622). It has the only pre-reformation stained glass in Scotland, still in its original position. One panel shows the arms of Mary of Guise, mother of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Following the Reformation, the Catholic chaplain to the guild was replaced by a Protestant. The building has served various roles over the centuries and remained in the possession of the Hammermen until 1857. During the period of the Covenanters, one of its more tragic duties was as the place where the bodies of the martyrs, executed in nearby Grassmarket, were brought and dressed for burial, including Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll and Dr James Guthrie.

It was too here that the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society was founded in 1841 at a meeting led by Dr James Abercrombie. The adjacent building was once known as the Livingstone Memorial Hall, in memory of the society's best known missionary David Livingstone.

The Mound

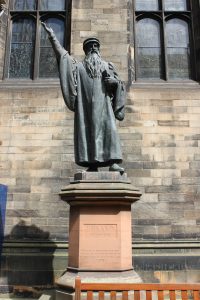

John Knox statue

Overlooking Princes Street and the Scottish National Gallery are two theological colleges virtually next to each other. New College occupies an impressive building in Mound Place and is the postgraduate School of Divinity of Edinburgh University. In the courtyard is a statue of John Knox in a striking pose, his right arm raised in preaching, the other holding a Bible with one finger inserted to mark his text. It was erected in 1896 by Scotsmen who appreciated Knox's legacy.

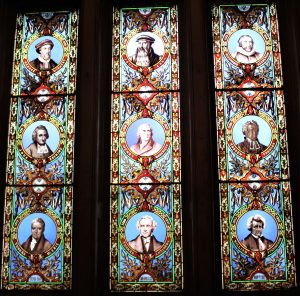

Next door, but technically in North Bank Street, is the Edinburgh Theological Seminary, training ministers for the Free Church of Scotland. Access is only by prior arrangement, but in the wood-panelled Presbytery Hall there is, at one end, a stained glass window with portraits of some of the most important figures in Scottish church history, and at the other, a remarkable painting of both artistic and historical interest. There is also a framed copy of the original National Covenant, bequeathed by the Earl of Dalhousie in 1874. Those depicted in the window include George Wishart, John Knox, Alexander Henderson, Andrew Thomson, Thomas Chalmers and John Erskine.

Free Church College window

The massive painting depicts what became known as the Disruption Assembly, by which the Free Church of Scotland separated from the Church of Scotland over the right of congregations to appoint their own ministers, irrespective of the wishes of the local patron. The picture is by David Octavius Hill, who was among those present. As well as a gifted artist, Hill was also a pioneer photographer and friend of Henry Fox Talbot. At the suggestion of the physicist Sir David Brewster, also present, he cooperated with Robert Adamson to photograph several hundred of the delegates, from which he obtained good likenesses. This may have been the first time photography was used in support of painting, and certainly the first time on this scale.

The painting is titled The First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, Signing of the Act of Separation and Deed of Demission at Tanfield, Edinburgh, 23 May 1843. Central to the group is the key figure of Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847), much respected by all sides for both his learning and character, who became the first Moderator of the Free Church. Also prominent is Thomas Guthrie (1803-1873), disciple and successor to Chalmers. Of particular interest are laymen depicted here, distinguished in many academic disciplines, illustrating Scotland's well deserved reputation for intellectual achievement in the 19th century: anaesthetist Sir James Young Simpson, physicist Sir David Brewster, geologist Hugh Miller, pioneer of savings banks Henry Duncan and missionary educationalist Alexander Duff. Altogether, Hill captured likenesses of 474 of the delegates (including himself!) out of about 1,500, and the picture took 23 years to complete. Modern commentators may deplore the few women in the portrait, mostly wearing bonnets and at the back, but pictures reflect their own time, not the sensitivities of later generations. Several of those depicted, including Miller, Simpson and Hill himself, were prominent lay members of St Columba's Free Church nearby.

New town

Edinburgh New Town is rightly considered a triumph of architecture and town planning and is now a World Heritage Site. It was principally conceived by the architects James Craig (1739-1795) and Robert Adam (1728-1792). Begun in the 18th century after the Union of England and Scotland, the street names reflect the Hanoverian kings, queens and politicians of the period - George Street, Hanover Street, Frederick Street and Charlotte Square. From the 18th to the 20th century, many significant figures of the Scottish church lived in this area. Scotland does not display the blue plaques familiar in London, marking the former dwellings of famous people. Those remembered are more likely to be scientists, doctors or writers rather than church ministers.

Thomas Chalmers statue

Thomas Chalmers lived at 3 Forres Street (EH3 6BJ), a handsome four-storey terraced house, with decorative iron balconies on the first floor. He also has a statue in George Street, at the junction with Castle Street. It shows him with his Bible held in both hands, reflecting his role as a highly respected theologian, professor of divinity and first moderator of the Free Church of Scotland.

Further along George Street is the church of St Andrew and St George, with a spire in several tiers like a wedding cake, four Corinthian columns and other classical features. This was the scene of the opening events of the Great Disruption. On 18th May 1843, 121 ministers and a number of elders left the Church of Scotland General Assembly held here, and walked down the hill to Tanfield Hall in Canonmills, where the Disruption Assembly was convened, with Chalmers in the chair. A few days later, there was another meeting for the Signing of the Deed of Separation. It was eventually signed by 474 ministers, a significant proportion thus leaving to become the Free Church of Scotland. The scene was depicted in a famous painting by David Octavius Hill, now in the hall of the Edinburgh Theological Seminary.

Church of St Andrew & St George

The Disruption was over the Patronage Act of 1712, which gave authority to local landowners to choose the pastors, which undermined the democratic nature of the Presbyterian Church. Debates over this issue had simmered on for over a hundred years, but the Disruption came to a head over the Strathbogie incident, in which a pastor who had been rejected by the congregation was forcibly reappointed by the civil magistrate.

Birthplace of R. M. M'Cheyne

Andrew Mitchell Thomson, a much respected Church of Scotland minister, lived at 29 Melville Street, solidly built in stone, with steps to the front door, an iron archway and first floor balcony. Thomson was minister for a time at Greyfriars church. He died too soon to become involved in the Great Disruption and is buried at St Cuthbert's Church at the west end of Princes Street. Because of its topography, the burial ground here is terraced, and Thomson lies on one of the lower levels, but its location is marked on a plan at the church.

14 Dublin Street was the birthplace of Robert Murray M'Cheyne (1813-1843), minister at St Peter's Church, Dundee, renowned for his life of holiness and dedication, which came to a tragically early end through typhus before the age of 30. The house is in a terrace of fine residential properties, mostly five storeys, including the basement. Number 14 looks as if it might once have been a side entrance to the present number 16, but the numbering may have changed. There is no plaque.

The Georgian House, 7 Charlotte Square.

Georgian House interior

This splendid property is now owned by the National Trust and open to the public. It has been restored in the style of Robert Adam and furnished appropriately. In one room an audio-visual display describes the family life and domestic arrangements of the first residents. Displays in other rooms recall the lives of other owners or occupants over the last two centuries. (The adjacent property, even more impressive, just happens to be Bute House, 6 Charlotte Square, official residence of the First Minister of Scotland!)

On the second floor is a display describing the life of Alexander Whyte (1836-1921), a Free Church of Scotland minister, who served for many years at St George's Free Church (now Charlotte Chapel). He lived here from 1889 until his death, although his wife Jane and family continued to occupy the property until 1927. They had eight children, several of whom had distinguished careers, one as an MP, another as an eminent scientist.

In 1913, Whyte and his wife played host to Abdul Baha, son of the founder of the Baha'i faith, who had spent several decades in prison in the Middle East, because the new religion was seen as a rejection of Islam. Mrs Whyte had met Baha on a trip to Palestine in 1906, and was involved in organising his visit and arranged for him to address a number of meetings in Edinburgh. While clearly not accepting all Baha's beliefs, it seems the Whytes had a mutual interest in promoting freedom of expression for all religions especially in Muslim countries.

Whyte was a fervent evangelist, but also had a broad cultural background, not often seen in the evangelicals of his day. Besides his relationship with Abdul Baha, he lectured on Dante and corresponded with John Henry Newman. He welcomed the American evangelists Moody and Sankey to the city in 1873, and from 1909 to 1918 was principal of New College.

Charlotte Chapel

Charlotte Chapel

This impressively large church stands on the corner of Shandwick Place and Stafford Street. Its architecture, striking both inside and out, is 19th century Roman baroque revival, with a later Venetian tower. The building has undergone various changes in name and denomination during its history. Formerly know as St George's West, or Free St George's, it was here that Alexander Whyte exercised his ministry from 1870 to 1896, succeeding the equally distinguished R. S. Candlish.

The present congregation is a free evangelical church, with a thriving ministry in central Edinburgh. They have evolved from a Baptist church founded in 1808, which has occupied buildings in various locations in its history, including Charlotte Square, hence the name. Former ministers of Charlotte Chapel, although not in its present location, include W Graham Scroggie (1916 to 1933) and Alan Redpath (1964 to 1968).

Dean Cemetery

Grave of Brownlow North

Just to the west of Edinburgh, the charming Dean Village lies in the deep valley of the Water of Leith and just beyond is one of the city's main cemeteries. Here, the well-to-do professional classes are often remembered with elaborate headstones and memorials, the inscriptions giving warm appreciation of their achievements. It seems as if every other citizen was a doctor, lawyer, diplomat or scientist. Alexander Whyte is buried here but our visit did not allow time to locate the site.

We came in search of the grave of Brownlow North (1810-1875). Marked by an obelisk, it lies along the southern boundary of the cemetery, to the left of the path. North came from an aristocratic ecclesiastical family (his grandfather of the same name had been Bishop of Winchester), but until his mid-forties led a life of careless self-indulgence, marked by party-going, hunting and gambling. In 1854, he experienced a dramatic conversion when suddenly taken ill while playing cards. Thereafter, he became an effective evangelist, greatly used in the Northern Ireland revival of 1859. As his epitaph declares ...he preached the gospel with singular power, and was greatly honoured in winning souls to Jesus.

Robert Kalley's grave

Scotland is famous for generations of medical missionaries and few exemplify that tradition better than Dr Robert Kalley (1809-1888). Born and educated in Glasgow, Kalley became a ship's doctor and then settled in Madeira on account of the health of his first wife, who suffered from TB. During his eight year residence, he founded a small hospital, several elementary schools and the Presbyterian church of Funchal. Catholic opposition, however, forced Kalley and his converts to leave. While the converts eventually found a home as a Portuguese-speaking colony in Jacksonville, Illinois, Kalley moved to Brazil with his second wife in 1854. Here, there was still resistance to Protestantism, but he became a friend of the emperor Pedro II and was instrumental in founding Crista Evangelica churches based on the Presbyterian model. Returning to Scotland in 1876, Kalley became Director of the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society. His grave is on the hidden lower terrace of the cemetery.

South Edinburgh

Liddell's Olympic race

At the point where Bruntsfield Place becomes Morningside Road is the Eric Liddell Centre (EH10 4DP). Named after the famous athlete and hero of the film Chariots of Fire, this church building has now been converted for use as a social centre, providing services for families, dementia sufferers and the elderly and disabled.

Inside, there is a display of books either about Liddell or written by him, and along a corridor at the back a series of photographs of scenes from his life. These include school and family groups, and images of his athletic career, when he famously refused to take part in his best event because heats were held on a Sunday, but still managed to win a gold medal in another event at the 1924 Paris Olympic Games. There are also scenes from his life as a missionary in China.

Grange Cemetery

Thomas Chalmers memorial

Located on Beaufort Road, about a mile south of the city centre, Grange Cemetery has the tombs and memorials to key figures in 19th century Scottish church affairs, particularly those relating to the formation of the Free Church of Scotland. Against the north wall, about halfway along, is a plot with the graves of Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) and members of his family. The central memorial stone is to Chalmers himself, giving dates but no biographical details. Other stones name his wife, Grace Pratt, his children and other relatives.

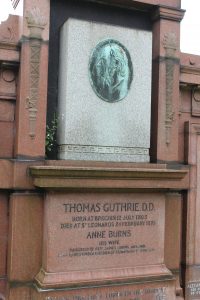

Whether by accident or design, Chalmers' colleague and co-leader of the Free Church of Scotland, Thomas Guthrie (1803-1873) lies in an exactly corresponding position against the south wall. He has an even more impressive rose granite memorial, elaborately carved and with an inset profile portrait. His wife Ann Burns is also mentioned, and side panels list the names of many other relatives.

Grave of Thomas Guthrie

At the entrance to the cemetery, a plan shows the location of the graves of prominent citizens, including Chalmers and Guthrie, but fails to mention that of Alexander Duff (1806-1878). He lies close to the path on the north side, just east of the path running north to south. There is a square stone monument with his name and that of his wife Anne Scott Drysdale and the simple inscription First missionary of the Church of Scotland to India. This hardly does justice to Duff's achievements, especially in education. He founded schools and promoted the teaching of a modern curriculum in India, alongside the Bible, using English as the medium to avoid the complications of local dialects. He was one of the founders of the University of Calcutta, and from 1867 held the chair of evangelical theology at Edinburgh University.

Immediately opposite the entrance to the cemetery is St Catherines' Argyle Church (EH9 1TY). The first minister here, from 1866 to 1887 was the hymnwriter and preacher Horatius Bonar (when the church was called the Thomas Chalmers Memorial Church). He lived during this time at 10 Palmerston Road nearby, which has some impressively large houses. On his death in 1889, for some reason he was not buried here, alongside many of the other Free Church pioneers, but at Canongate Kirk on the Royal Mile.

Newington Cemetery

Grave of Dr John Ross

About a mile from the Grange burial ground lies yet another hero of the 19th century Scottish missionary movement. Educated in Glasgow and Edinburgh, Dr John Ross (1842-1915) travelled to China in 1872 and was based in Mukden (now called Shenyang) in the north of the country. He established a church just outside the east gate of the city as churches were not allowed within the walls.

Meeting traders from Korea, Ross realised this was an opportunity to bring the gospel to that country, where access for Christian missionaries was very limited. He made a Korean translation of the New Testament, which, along with other Christian literature, could be carried by travellers between the two countries.

Ross lies on the east side of the main north-south path in the cemetery (EH16 5DT). There is also a plaque to his memory at Mayfield Salisbury Parish Church, West Mayfield (EH9 1TQ)